Trust in Science: Accessibility, Persistence, and the Public Good

I had the privilege last week of speaking at the International Association of Universities conference, held at the University of Rwanda. It was a long and at moments difficult journey, but well worth it for the conversations that took place there. The conference theme was "Building Trust in Higher Education" -- a goal that has formed the basis for my last two books -- and I was invited to speak as part of a plenary panel focused on "Trust in Science," which enabled me to talk a bit about the work that we're doing at Knowledge Commons to make our platform a trusted, nonprofit, community-governed partner for institutions of higher education around the world. My presentation is below; I'll look forward to continuing this discussion.

I’m delighted to be here and to have this opportunity to talk a bit about trust in science. I want to start out by noting that "trust" is an awfully big word, especially as applied to higher education. For us to cultivate trust in the work we do in universities, we first have to demonstrate ourselves and our institutions worthy of that trust. It’s not necessary for me to detail all of the ways that trust is being challenged today, but I’ll note that some of these challenges derive from ongoing issues in the world around us, as misunderstandings of the motivations of scientists and ideological conflicts surrounding inconvenient research combine to produce widespread dismissals of the knowledge produced through scientific research, as well as growing concerns world-wide that politicians might interfere with scientific research or censor its results in highly damaging ways.

However, some of the challenges we face are of our institutions' own making. We might immediately think of the ongoing reproducibility crisis, or varying kinds of researcher malpractice that have created understandable concerns about the integrity of scientific work. But we must also consider the ways that many of our institutions have excluded the vast majority of the world’s populations from participating in the knowledge creation processes that form the heart of research. In the United States, I frequently hear scholars and administrators lament the fact that the general public does not understand the good that our faculty and our institutions do – but it’s hardly surprising, when the public cannot see the work that we do, and therefore cannot understand our motivations for doing it or the ways that our work creates knowledge that supports healthy, sustainable communities. Restricting our work to exchanges among experts breeds distrust by keeping our reasoning and our results hidden from view.

I want to argue today that building trust in science today has two major prerequisites: accessibility and persistence. When I talk about accessibility, I mean in part to point to open access, which attempts to ensure that the results of research can be found by anyone. But I also mean that research needs to be accessible in another sense, in adopting a register of communication that can be broadly understood, ensuring that the work can not just be downloaded but read and engaged with. There are of course valid reasons that researchers use a professional vocabulary with one another, but that vocabulary often prohibits real engagement on the part of many of the publics that our institutions serve, publics who might be interested in what our institutions do if they were invited in. Many of our institutions and our funding bodies strongly encourage researchers to engage with broader audiences, but we need to ensure that doing so is integrated into our institutional reward structures, and that the work of translating advanced research for broad consumption is recognized as real work. If universities encourage and reward broader impacts by supporting researchers in making more of their work – its processes as well as its results – fully accessible, we will have the opportunity to cultivate public trust by building a richer understanding of what it is that researchers do, and why they do it.

At the same time, we need to think about the persistence of the work that researchers do: not only does research need to be made accessible, but it needs to remain accessible, even in the face of the significant challenges to science that many of our institutions are facing in the current political moment. Researchers on our campuses are investigating all manner of inconvenient questions – about climate change, about global inequities, about the history of colonialism and the forms of oppression that it has created – and much of this research is at risk of disappearing. Some of this risk comes from direct censorship, as we have seen governments demanding the removal of work that it doesn’t like from journals, websites, and databases and defunding the research that makes that work possible. Some of the risk comes from shifting corporate priorities, as the for-profit companies that still control most of the scholarly communication infrastructure have goals and motivations and requirements that are often very different from those of our institutions. Ensuring that today’s research results remain available to be built on tomorrow will require all of our institutions to think seriously about the infrastructure on which their researchers’ work is hosted: who owns and operates that infrastructure, and to what ends. Is the most important goal of the infrastructure's owners sharing knowledge toward the creation of a better world, or is it returning value to shareholders?

That's a pretty crude distinction to draw. I'm sure that all of us know of nonprofit organizations that operate as extractively as many profit-driven companies, as well as corporations that operate with a clear sense of their responsibility to the public good. But it is essential -- and especially right now -- for institutions of higher education to insist that the partner organizations to which they entrust the knowledge they produce have goals and priorities that align with their own. This is true not least because of the non-reciprocal material relations between our institutions and too many of the infrastructure providers on which we rely: our researchers and our institutions freely give them the gift of our work, our labor, our time and attention, and in return they charge us, over and over again. When they can't charge us to access the work, they charge us to publish the work that we have done, and they charge us to access the data they have harvested about that work.

There are alternative models for scholarly and scientific communication that can help researchers make their work both more accessible and more persistent, however. These alternatives include publishing cooperatives, open repositories, and more. I want in the time I have remaining to tell you a bit about the project that I've had the privilege of working to build over the last ten years: Knowledge Commons.

Knowledge Commons is an open-access, community-governed, nonprofit network hosted by Michigan State University, on which knowledge creators across the disciplines and around the world can deposit and share their work, build new collaborations, and create a vibrant digital presence for themselves, their teams, and their projects. Knowledge Commons is guided by the FAIR principles for open science, ensuring that the products of research entrusted to us are made findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, and is committed to living out the Principles for Open Scholarly Infrastructure.

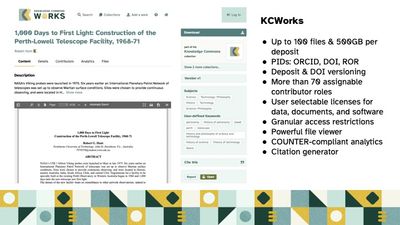

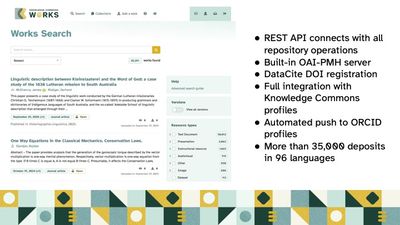

The Commons brings together a next-generation repository, KCWorks, which is built on InvenioRDM, with a robust researcher profile system and a suite of WordPress-based publishing and communication tools. The Commons hosts nearly 60,000 researchers, instructors, practitioners, and students who are sharing and preserving their work. KCWorks registers DOIs via DataCite for every deposit and then versions those DOIs as works are updated, and it offers a very wide range of contributor roles, licenses, and subject headings that enable our metadata to serve nearly any purpose.

KCWorks is highly interoperable, thanks to its strong REST API that connects with all repository operations and its built-in OAI-PMH server, allowing the repository's metadata to be readily consumed by a range of open services across the web, dramatically increasing the discoverability of the work researchers deposit with us. Upon deposit, that work is automatically pushed both to the contributor's profile on the Commons and to their ORCID record, and it can also be shared to various social media platforms.

The Commons has to this point focused on creating greater accessibility for the products and processes of research, but if we are to succeed in transforming the global research ecosystem into one that is worthy of the public trust, however, we must face two key challenges. The first has to do with persistence. Though the project and its team are hosted by Michigan State University, the technical infrastructure we use to support the project is not; the university's computing and data infrastructures are not currently able to support our work. Instead, we are hosted on Amazon Web Services -- and as we found out yesterday, as robust as AWS is, it isn't immune from major technical failures. On top of which, AWS has become a massive consumer of university resources, as well as being part of a corporation that has not proven itself to have the public good as a primary driver. One might begin to wonder what could be possible if a collective of institutions were to come together and put the resources they spend in Silicon Valley toward developing academy-owned shared infrastructure, allowing higher education to take greater control of its own technological future. And what might become possible if that network of institutions were truly global, enabling the research that is developed and made available in one area of the world to be mirrored all over the world, allowing science to evade censorship wherever it might surface?

The Knowledge Commons team submitted a pre-proposal describing the first steps for such a network earlier this year to the Trust in American Institutions Challenge hosted by Lever for Change, and while we did not advance to the final round of consideration, the group of collaborating organizations that signed on to pursue this project -- including the Association of University Presses, the Association of Research Libraries, Jisc, the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association, OAPEN, and more -- are still interested in pressing forward with it. We'll be meeting later this month to discuss our next steps.

But key among those next steps is of course finding the resources to accomplish something so enormous, especially at a time in which so many of our institutions are facing austerity measures. Which points to the second challenge for Knowledge Commons in becoming a research platform worthy of the public trust: financial sustainability. We are committed to keeping the Commons free and open for any individual user to join the network, create a profile, share their work, and participate in the collaborations we make possible. In order to do so, we need universities and other research organizations to join the Commons consortium, investing their resources in a community-governed alternative that can make open science genuinely open to all. The future of the Commons depends on the will of that collective, in more ways than one.

- ← Previous

Learning - Next →

Join the KC Coalition